- Home

- Jenny Hval

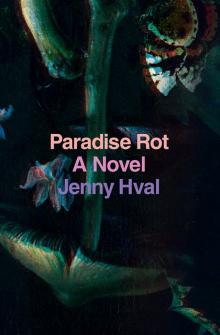

Paradise Rot

Paradise Rot Read online

PARADISE ROT

PARADISE ROT

A Novel

JENNY HVAL

Translated by Marjam Idriss

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA

This English-language edition first published by Verso 2018

First published as Perlebryggeriet

© Kolon Forlag 2009

Translation © Marjam Idriss 2018

Lyrics to ‘Alison’ reproduced by kind permission of

Neil Halstead and Cherry Red Songs

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-383-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-384-2 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-385-9 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hval, Jenny, 1980– author. | Idriss, Marjam.

Title: Paradise rot : a novella / by Jenny Hval ; translated by Marjam Idriss.

Other titles: Perlebryggeriet. English

Description: London ; Brooklyn, NY : Verso, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004566 | ISBN 9781786633835 | ISBN 9781786633859 (UK EBK)

Classification: LCC PT8952.18.V35 P3713 2018 | DDC 839.823/8 – dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004566

Typeset in Electra by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

Milk and Silk

The Chest

The Shadows

The Apartment

The Apples

The Fruitpearls

The Double Sleep

The Moonlip

The Spores

The Brewery

Pym

Seasnails

Prune Skin

The Honey Mushroom

The Lighthouse

The Storm

Goldapple Stems

Eden

Black Fruit

Under the Sea

Epilogue

PARADISE ROT

Milk and Silk

THERE, AND NOT there.

Outside the hostel window the town is hidden by fog. The pier down below dissolves into the colourless distance, like a bridge into the clouds. At times the fog disperses a little, and the contours of islands appear a little way out to sea. Then they’re gone again. There, not there, there, not there, I whisper, leaning against the window, drumming my fingers against the glass in time with the words, dunk, du-dunk, as if I’m programing a new heartbeat for a new home.

So I sat that first morning in Aybourne, leaning against the windowpane, forehead flat on the glass. My shoulders ached from carrying my backpack. I hadn’t taken it off on the train from the airport. I just stood and held on tight to all my things while strange stations and billboards in bright colours whizzed past. The straps gnawed into my shoulders while I counted the stops to my destination. I studied how people would, instinctively, pull the handle to make the doors open at just the right time. I had tried to absorb the technique before it was my turn to get off, so that no one would realise this was my first time on this train. When the time came, however, I stood by the door and pulled the handle to no effect. A woman in her forties tapped my shoulder – The other side, love – and I just about managed to get off the train in time. After that I stood on the platform for a moment while a stream of rush-hour passengers passed me, like a river parting itself around a small rock.

The trip had been hard. I had too much luggage, my coat was too big, and I had become distressed in the duty-free shop, which was permeated by the smell of sickeningly sweet perfume. In the hostel my body became light and insubstantial, and I imagined that I, too, was being swallowed by fog, that I was dissolving in it. The remnants from my journey lay tossed around me: tickets and promotional leaflets on the table, an English fashion magazine on the bed, salt and pepper packets on the floor. The sound of cars on the street outside and a fly that buzzed under the curtains replaced the echo of that strange voice that had announced doors closing over the train’s loudspeakers. I closed my eyes. The glass was cold and dry. When I stood up to take a shower, I had left a blurry oil-print on the pane.

The shared bathroom was across the hall. It was a dirty and colourless room with grey-yellow wallpaper and dark carpeted floors. The bathtub’s enamel had faded and grown dull, and when I washed my hands there was no mirror over the sink, only a dark square impression and a rusted screw where a frame once hung. I found the mirror-glass on the cistern behind the toilet bowl, as if someone had used it to watch themself masturbate. Now it reflected my belly and hips, and I stood there like a man and unzipped my trousers with my front facing the toilet bowl. It felt almost strange not to have a dick to pull out through my fly. When I rolled my jeans and pants down my thighs, the dark triangle of pubic hair looked strangely empty, like a half-finished sketch. I turned around, sat down on the toilet seat and looked down between my legs, where a thin stream of urine trickled into the bowl. The dirty-white porcelain was tinged with acrid yellow. Almost a shame to flush away all that colour, I thought.

Afterwards I sat by a corner table in the breakfast hall. Breakfast was nearly over, and a bored waiter was stacking bowls filled with packets of cheese and jam in a refrigerator. A loud group of golfers sat nearby. Some of them had already put on caps and gloves, and they drank their coffee from paper cups with white-gloved hands. Long black golf bags were propped against the wall. The room was emptying and yet it felt full. The smell of the old smoky carpet mingled with the coffee. The sugar cubes in the bowl were covered in dust.

As I stepped out into the street, the morning light broke through the fog, catching on the tram tracks. I followed the tracks to the nearest stop, noting the trash on the pavement, a discarded juice carton and greasy pages of newsprint. My blurred reflection appeared in shop windows beneath unfamiliar English signs: Newsagent, Chemist, Café. When the tram came, that too bore a name I did not recognise, Prestwick Hill.

The carriage was half-full. Two rows of seats lined its sides, facing each other. A large inebriated man sat at the back, alternating between snoozing and babbling to himself. Every time he fell asleep, he slipped a little further off his seat. When he wriggled back into position, his oversized and low-riding trousers slipped a little further down his hips. He wasn’t wearing anything underneath. The other passengers pretended not to notice. A few teens were chatting quietly, a girl read a magazine intently, and others stared out the window. I picked up my guidebook and turned the pages, but I couldn’t concentrate. Like everyone else on the tram my attention was on the man and his trousers. Sometimes people would exchange quick glances, and when his trousers finally slipped past his hips and down his thighs, an uncomfortable sense of solidarity formed in the carriage, one common heart beating quickly and awkwardly. No one looked at the man, and yet everyone saw at once a flaccid red limb protruding from his crotch like a parched tongue. Agitation spread between the seats; our bodies started to itch and sweat. I looked around, and everywhere nervous glances met my own. Finally, two newly arrived men went over to the man, helped him put on his trousers again, and threw him politely out at the next stop. I saw him rave through the high street, carving a wide path in the crowd. The passengers in the carriage exhaled. They could return to themselves, disappear into their enclosures

. I was alone again.

I got off the tram by a little park between big office buildings in the centre of town. The fog had finally lifted. Thick clouds were rushing far above my head, much higher and faster than the clouds at home, as if Aybourne were in a deep gorge. I had no plan and no map, so I sat down at a café and ordered what seemed easiest to pronounce. When my tea reached the table, they had put milk in the cup without asking, so much that the tea was completely white, but I didn’t say anything. On the street outside, autumn rain had begun to fall. Between the businessmen with umbrellas and newspapers over their heads, the asphalt was dotted, dark grey and then black and gleaming like snail skin. I pulled my knees up in front of me on my chair, as if I sat in a little lifeboat drinking my white tea. I tried intermittently to read a newspaper, but my English wasn’t up to it. Instead I watched the cars and listened to the rain through the open door. I listened to footsteps and to raincoat fabric rubbing against skin and cotton when people sat; to strange heavy coins that jangled over by the counter and cups clattering against saucers.

When I returned to the hostel that afternoon, a tall Asian girl stood by the counter. She looked confused. The receptionist tried to explain how to check in. ‘You need to sign your name here, please,’ she said with a sigh, but the Asian girl didn’t look like she quite understood. ‘But I have a room, yes … From the university,’ she said. A boy in a suit with an American accent tried to help, but the girl didn’t understand him any better, and she looked tensely down at the counter. I tiptoed past them, happy to see other foreign students. There were more in the communal area: two girls from Montreal playing cards and a pair of siblings from Madagascar taking turns to use the phone. Later in the night I heard all four of them arguing loudly in French, and when one of them slammed a door, the floors creaked. The matted grey-blue carpet sent heavy dust clouds into the attic air.

Throughout the night an icy ocean wind blew through the cracked window, and I woke up the next morning feeling like the cold had sunk into me, turning bone to wood and skin to sawdust, making me like Pinocchio. When I stretched, my shoulders creaked, and I put on several layers of thick clothes before leaving for breakfast.

The food in the breakfast hall was slippery and fluid: silky soft white bread slices that dissolved like candyfloss in my mouth. Glutinous jelly-like jam without seeds and of an uncertain berry flavour. Butter, smooth peanut butter, honey, milk, Marmite and ketchup. Soft rice puffs and soggy fried eggs. I remember everything at home as being textured: whole-wheat bread with hard crusts and coarse liver paste, the feeling of grains and fibrous meat swallowed with black tea, the whole lot going down your throat like wet gravel. Here, I chewed and only the sugar crunched. I sat poking a wet fingertip into the sugar bowl and then sucking on it, crushing the sugar crystals between my teeth.

The foreign students too were smooth and gleaming. May, the Asian girl (Chinese as it turned out), had thick shiny hair. David, the American boy, had a freshly ironed shirt neatly tucked into his trousers, and Ella and Lauren, the Canadian girls, smiled with straight white teeth. They spoke of their travels, the weather and each other’s cities in slow polite voices:

‘We’ve done Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, so pretty, Indonesia, Bali, awesome, and soon we’re going to South America …’

I had barely recognised them when I entered the breakfast hall, as if their faces had been wiped clean overnight along with the plates, eyes and lips scrubbed clean of honey stains and breadcrumbs.

May and I spoke a little after the others had gone out shopping. Her handshake was soggy and her skin felt smooth like the peanut butter on the white bread in front of me. She had served herself a huge plate of Coco Pops, a large mug of hot chocolate, a glass of milk and some bread.

‘European food,’ she said and smiled, while she used a spoon to scoop out a massive wad of butter from the butter dish, spreading it unevenly on the slice of bread. ‘I love milk,’ she continued. I smiled back at her and put my knife in a jar of peanut butter.

‘You like …’ May struggled to find the right word. ‘… Club?’

‘Club?’

‘Dancing …’ She slurped her cocoa.

‘Ah, nightclub,’ I said. ‘I don’t go out much.’

‘OK, yes. I like.’

‘Really? Do you go out much at home?’

‘Yes, me and friends. Dancing, singing …’ May tried to squeeze her spoon into a small pack of jam where it wouldn’t fit.

‘It’s easier with a knife,’ I said.

‘Oh,’ she said and blushed.

The university had left big envelopes in the reception, containing welcome letters, a map of the campus and information about the different trips and social events in and outside of Aybourne. The events had funny titles: ‘You Talkin’ to Me?’ was a class in conversational English, and ‘Fish’n’Chippin’ Aybourne’ was a fishing trip. The first event was called ‘Tackle the Town’. I hadn’t got round to checking what it was yet, but the other students at the hostel seemed so excited that I came with them. Alice, an American lady from the foreign exchange office, picked us up, and we got the tram down to a huge stadium where we watched a rugby match between two local teams. Alice showed us to our seats and said informative things like Here you see the Aybourne Dragons’ supporters with their green and white scarves, and of course an Aybrew ale, that’s our local beer. The students all went to the kiosk, where we bought our own Aybrews and little pies. My pie lay in my hand, lukewarm and dense. It looked like an inflated yellow beer cap.

‘What’s in the pie?’ I asked Lauren, one of the Canadian girls.

‘Kidney and brown sauce,’ she replied. I deposited the little kidney gently on an empty seat. Then we went back to our places and tried to find out which team was winning.

‘This is not like ice-hockey,’ giggled Lauren. She pointed out towards the pitch. ‘Look at those tiny shorts! They’re almost naked, yummy!’

Next to me, May smiled. I thought of the man on the tram, and wanted to tell her about him, but didn’t know what word to use. Penis, dick, cock? On the pitch men were throwing themselves at other men, and Alice waved her arms, yelling things like And here you see a maul … a maul is … Every time someone got a knee to the crotch or a foot to the chest, a shudder went through the audience, and I could feel that same shudder go through my own body, feel it lifting us for a moment before we slowly sank back into our seats.

After the match, empty Aybrew bottles and napkins, sweet wrappers and plates were left lying on the benches and on the street outside. In the town centre the shops were closed and the restaurants empty. The student group split. Alice got a tram to the beach, Ella and Lauren went to a pub, May went to meet the Chinese student society, and I walked slowly back to the hostel alone, headphones on. I felt a need for something familiar in the strange, dark streets, something from Norway, so I put on Kings of Convenience. They sang in harmony, one voice for each of the tram tracks that gleamed in the dark next to me. They sang slowly as I was closing in on the hostel by the pier.

Later I felt the walls of the attic close in, collapse around me and shut out the world. The music separated me from the sound of cars, wind, and my own steps.

In the middle of the night I heard May on the phone in the hallway. The sounds of her alien language bubbled, as if they came out of and into her mouth at the same time. Half asleep, I pictured the words as lines of knives and spoons. After she hung up, I heard her feet shuffle into her bathroom. There she pulled down her trousers and sat on the toilet seat. Urine streamed against the porcelain bowl. In the darkness I thought it sounded a little thick, as if warm milk was trickling out of her.

The Chest

THE NEXT DAY the weather had cleared and as I didn’t want to attend ‘You Talkin’ to Me?’ with the others, I decided to walk around Aybourne alone instead. I wandered along the tram tracks between whitewashed buildings and posters advertising cars, diet yoghurts and energy drinks. The sea followed me on the far side. Islands

that I could barely see the day before gleamed in the sunshine.

First I tried to reach the edge of town, but no matter what direction I walked I was forced to turn back. The last stop on one of the tracks ended at an orbital motorway that ran parallel to an electric sheep fence, and I could go no further. In the other direction I found a golf course that ran from the last of the town streets all the way down to the beach. Between the town and the golf course the broad South Gate motorway ran, and I couldn’t find a way to cross it. Eventually I walked upwards to the hills, towards the mountains. This route ended in a picnic area and some dustbins. After that there was nothing. Aybourne was beneath me, closed off in all directions, like a chest with no lid.

Next, I tried to find the university. When I got back into the town centre I pulled out the torn map I’d found in the dining room at the hostel. The map stained my fingers, as if it were melting. My fingertips were decorated with imprints of roads and parks. After a little while I had lost my way completely, and I was unsure whether the map I had was old or even if it was for the right town.

The third time I thought I’d found the campus, I realised that I was the one at fault, not the map. I wasn’t on university grounds but I had entered an overgrown garden. It lay by a gigantic grey brick building with archways at the entrance and a pointy Victorian clock tower at the top. This must be city hall, I thought, my finger still on the map, because that was supposed to be in front of the campus. And when I looked closely I could see a faded old engraving on the dark wall: City Hall. A narrow path twisted through the garden towards the archways and when I followed it I found an old sundial in the tall grass. It was around a metre tall, like a pulpit, and wrought in iron with ornaments around its foot. I bent over the sundial to see if it showed the time, but the long dark shadow from the clock tower fell across it, and the sundial was rendered useless, a face without features.

In between the archways someone waved at me, and I noticed the Canadian girls. I waved back and walked over to them.

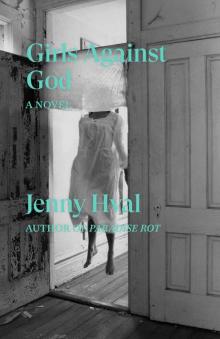

Girls Against God

Girls Against God Paradise Rot

Paradise Rot